I’ve written a few things for The Student recently about the painter John Bellany. He was a former art student at the ECA here in Edinburgh and he had an exhibition at the Scottish National Gallery just under a year ago. The show had a profound impact on me; I saw it just having moved to Edinburgh and there was something so blatantly Scottish about the works, which I found charming. Here’s the review I wrote of the show:

There’s something unerringly Scottish about the square above the Princes Street Gardens. Standing stoically to the south, the castle dominates our view. To the north, the Scott Monument pierces the horizon like a gothic spaceship while bagpipes comprise the soundtrack to the visit. For an artist so engrained in Scottish culture, it is apt that John Bellany’s comprehensive retrospective is found in The Scottish National Gallery.

The significance of this particular location is stressed in the exhibition. In a demonstration during his time at the ECA, Bellany hung his works from the railings outside the gallery – challenging the art world’s shifting centrality across the Atlantic towards distinctively American Abstract Expressionism. Endearingly showing signs of this tumultuous history, early paintings are often perforated with holes around the edges, or bashed in at corners as they were evidently carried down the mound. Despite his reaction to the new direction of his contemporaries, Bellany’s large-scale oils refrain from nostalgically harking back to the past. His references to Delacroix, Titan and Rembrandt exude timeless grandeur.

That’s not to say Bellany’s work lacks the energy of the age. Becoming aggressively gestural during his period of intense alcoholism and inner turmoil, the unsettling symbolism and violent brushwork is like watching someone’s self-destruction. Yet his paintings remain ferociously attractive. Teetering wildly on the edge of abstract expressionism, the movement Bellany desperately wanted to escape from, this is his moment of crisis.

Then you reach the Addenbrookes Hospital Series. Following an emergency liver transplant, Bellany painted an astonishingly fragile collection of watercolour self-portraits from his sickbed. Personal and honest, Bellany’s paintings return to his earlier philosophy and are serenely self-assured.

His most recent paintings have come full circle. Reexamining port scenes at Leith yet with an expressionistic heightening of colour, there is renewed appreciation of natural beauty, of his familiar hometown. His most recent painting finished in June 2012, a self-portrait celebrating his 70th birthday, comprehensively sums up his life. There are tinges of humour, dressed in black tie after he famously boasted he could paint with no mess, yet the gaunt face beneath his elbow, the wild brushstrokes, remain unnerving reminders of his riotous history.

A year later, Bellany died. I found out while I was in Tate Britain in London – on show, surrounded by memorial bouquets, was Bellany’s final ‘Birthday Portrait’. I first saw the same portrait a year ago in the Scottish National. Here’s the piece I wrote about it:

It is fitting that what was to be John Bellany’s last major exhibition was held at the National Gallery of Scotland last winter. From finding his early inspiration from the fishing community of Port Seton in the outskirts of Edinburgh, via his rebellious days as genre-defying art student at the ECA to his final colourful and uplifting depictions of Leith and his funeral at St Giles’ Cathedral on the Royal Mile, Bellany’s life and work has always had a distinctively Edinburgh-centric feel.

Yet it would be hard to miss the irony of the setting for his final exhibition that closed last January. As a student at the ECA, Bellany protested against increasingly American influence of Abstract Expressionism at the very gallery in which his work would go on to be exhibited some fifty years later. Joined by fellow art students, the painter chained his expressively realist works to the railings outside the gallery demanding attention for his own more figurative style.

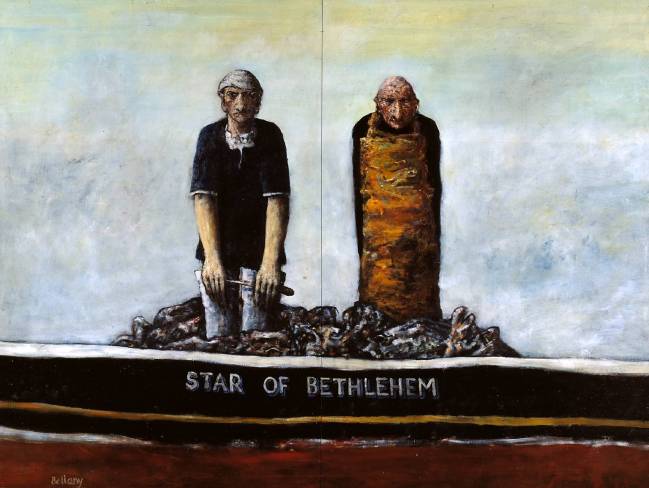

Bellany was forever paddling upstream against the wave of non-figurative representation that perhaps characterised his generation. As a student in the 60s his work consisted largely of paintings of the ports and their inhabitants around Edinburgh; they are markedly representational and attest to Bellany’s prowess in observation. His early works have an air of stoicism, a majesty that perhaps hints at an enduring significance to his work within the contemporary canon.

Bellany’s self-portraits are perhaps what may remain most celebrated. His ‘birthday’ paintings, completed each year, along with his hospital series, produced while still in hospital after an emergency liver transplant in the 80s, document both his changing physical appearance and his riotously oscillating psychological state.

There’s something to be said for self-portrait painting today. In the age of the ‘selfie’, the immediate gratification of an instant ‘self portrait’, on Snapchat or on Photo Booth, might just be making the practice of portrait painting a little obsolete. However, the ‘analogue selfie’, as Joe Moran in The Guardian dubbed painted self-portraiture earlier this week, still has much with which to commend itself. Bellany’s hospital series convey more than a photo ever could; the delicate watercolours reflect his teetering physical and mental condition. The last in his birthday series, completed for his seventieth birthday last year, conveys a great deal about Bellany. Paintbrush in hand, dressed in black tie, his final portrait reminds us of both his penchant for figurative representation and his own turbulent past.

Bellany, who died in the last days of August, was found paintbrush in hand. A metaphor for the death of painted portraiture? Let’s hope not.

Points in your life are often marked by repetition. I was recently talking to my friend Ella about this. What better way to recognise the passing of a year than by revisiting the work of someone you really admire?